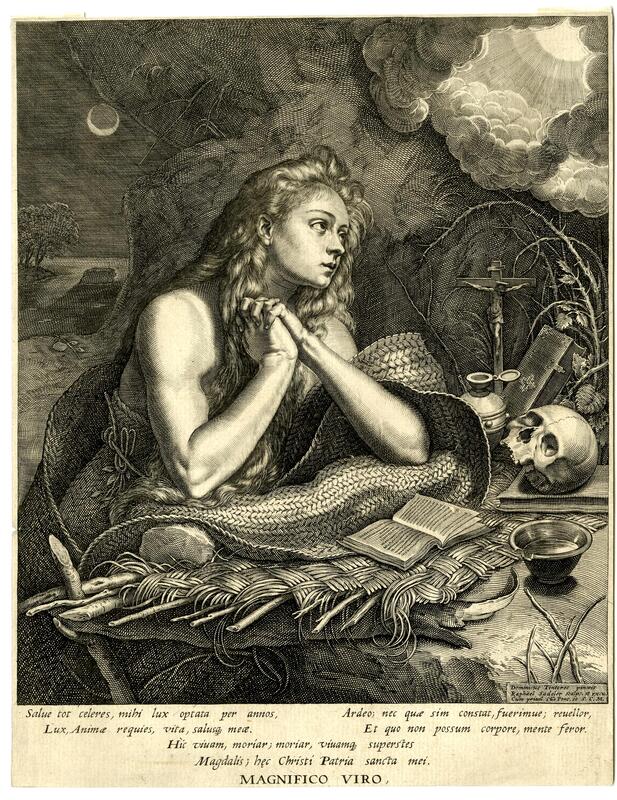

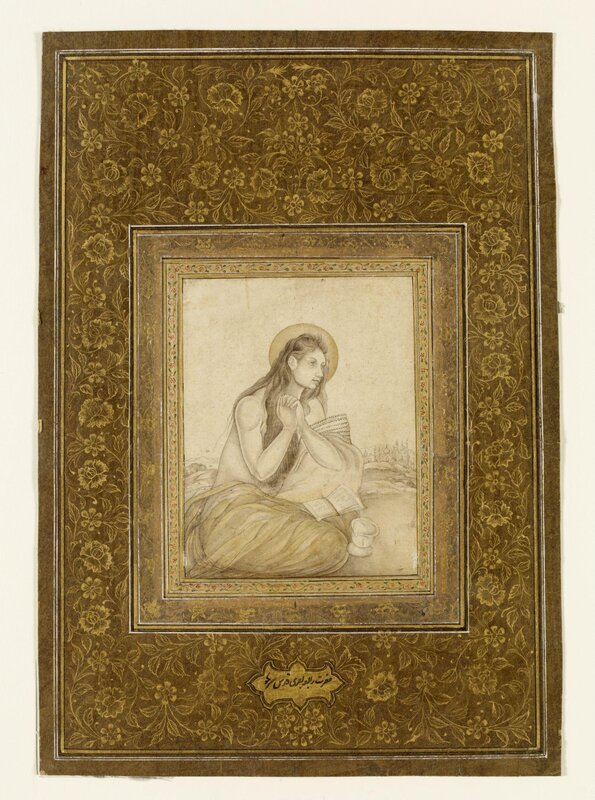

| Domenico Tintoretto (1560–1635): Penitent Magdalene, c. 1598-1602, oil on canvas, Capitoline Museums, Rome. Raphael Sadeler I (c. 1560/61-1628/32): The Repentant St. Mary Magdalene, engraving, 1602, this impression in the collection of the British Museum. “Lady Ra'aba of Basra,” by an unknown 17th century artist, India, Mughal Empire, ink, gold and watercolour on paper, Victoria and Albert Museum, London. | "Lesser artists borrow; great artists steal." — various attributions, including Picasso and Igor Stravinsky The idea of intellectual property theft is a fairly recent phenomenon. Today we recognize that straightforward copying of another’s work is theft, and that appropriating the work/style of another culture can be a repeat of colonization. However, look through art history, and you will find many an homage, let alone outright steals. At the time, not necessarily considered wrong, so long as you weren’t representing your own work as the original work of another (aka forgery). Sometimes, one homage can lead to another. In Europe, engravings provided a cheaper alternative to fine art, disseminating the artist’s work through many countries, not only European ones, even traveling as far as the Mughal Empire of India. We see the progression in these three works. The Penitent Magdalene became a popular theme in European art during the Renaissance and Baroque eras. The gospels tell the story of Mary Magdalene: a woman Jesus delivers from 7 demons. She becomes His follower, then one of the women present at the Crucifixion and then the first of his followers to encounter Him after His Resurrection. Over time, her story merged with this one: “And there was a woman in the city who was a sinner; and when she learned that He was reclining at the table in the Pharisee’s house, she brought an alabaster vial of perfume, and standing behind Him at His feet, weeping, she began to wet His feet with her tears, and she wiped them with the hair of her head, and began kissing His feet and anointing them with the perfume.” — Luke 7:37-38 (NASB2020) Later, this story merged with that of another Mary, the 4th Century desert ascetic Mary of Egypt, whose story pops up in a 7th century biography: a prostitute whose passionate embrace of the Christian faith impelled her to live the life of a hermit in the desert, devoted to prayer. In 591 AD Pope Gregory the Great combined all three stories in a sermon. And so the matter rested until Pope Paul VI officially ended the tradition in 1969. Never described by name in the gospels as a prostitute, this detail became imbedded in her story over time. Hence the theme of the Penitent, the Repentant Magdalene, still in sorrow for her alleged sins. And so, by way of an engraving based on Domenico Tintoretto’s original painting, we find a depiction of Rabiʿa al-Basri (717–801 C.E.). “Born in Basra in the 8th century of an impoverished family, orphaned and sold into slavery, Rabia al-Adawiyya… rose to become one of the greatest Sufi teachers. An extraordinary kaleidoscope of myth and reality, of imagination and fact... is it not of importance that a woman of such stature and independence of mind existed so early in the story of Islam, to show what women could be, and how they could be regarded?” https://islam786books.com/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=86_236&products_id=5567’ The Mughal artist in no way intends to conflate the Magdalene’s story with that of his own Saint. He translates the traditional Renaissance imagining into a story from his own culture. The Mughal artist’s work — an example of colonization of his culture by European models? One response to that question: “The Mughal response to European art was not slavish imitation but creative reinvention.” https://www.asianart.com/articles/minissale/ #domenicotintoretto #magdalene #magdalane #mughalart #renaissance |

|

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

November 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed